You name it. 2022 was the worst year for [Insert favorite Asset class] since [Insert historic year], and you’re probably correct. One that’s commonly quoted is that it was the worst year for the 60% Stock / 40% Bond portfolio since 1936. We can agree that 2022 was a painful year for most asset classes. Inflation accelerated for the better part of the year, and Central Banks, globally, got serious about addressing it.

Just over a year ago, the U.S. economy was booming, job openings were abundant and difficult to fill. Housing was setting price and sales records, and goods inventory was nonexistent for items from cars to furniture.

We enter 2023 with fear and pessimism in the air. Inflation, job loss, bankruptcies, and debate of recession on the horizon populate the headlines. The AAII (American Association of Individual Investors) Sentiment Survey offers insight into the opinions of individual investors, depicted in the chart, below. Individual investor pessimism in 2022 reached levels typically seen only during the worst of recessions.

In response to historically fast rise in inflation, the Federal Reserve completely changed its stance on monetary policy from the extremely accommodative one in place since the onset of the pandemic. The Federal Funds rate of 0.25% at the beginning of 2022 was increased to 4.5% in one of the fastest rate hiking periods in history. In fact, inflation seemingly shocked the Fed so much, that in May 2022 Chairman Jerome Powell communicated that a 75 basis point rate hike was not being ‘actively considered’, then went on to increase rates by 75 basis points at each of the next three meetings.

Additionally, the Fed’s bond buying policy (Quantitative Easing (QE)) shifted to a bond selling (Quantitative Tapering (QT)) policy. For reference, when the Fed buys bonds, it is injecting liquidity to the economy (accommodative policy), and vice versa when selling bonds (restrictive policy).

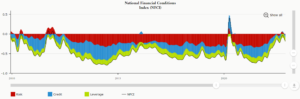

This shift to a severely restrictive policy resulted in some of the tightest financial conditions of the last decade, with hopes of removing ‘excess financial slack’ present in the economy, causing inflation.

The economic slowdown that we’re now experiencing is one that is ‘engineered’ by the Fed. Due to the restrictive policies in place and tight financial conditions that have been instituted, we see a reduction in spending, production etc. that were inflationary consumer habits. Higher interest rates cause monthly payments on big ticket items (i.e. housing and cars) to increase, therefore resulting in a slowdown in purchases. Energy costs spiked in the early half of 2022, though are mostly below the levels entering that year (factors outside Fed policy have also affected Energy over the past year), further easing inflation metrics.

These dynamics of easing demand for goods are allowing the economy to rebalance itself, while for the time being not causing a systemic risk that can ‘break’ the economy leading to severe recession. Forecasters and the media often refer to the Fed’s ‘soft landing’ as the ideal outcome where the Fed is able to institute a restrictive monetary policy to reduce financial excess without causing a recession, or a mild one if so. It should be noted that this outcome is highly elusive as the effects of policy take time to be felt through the system, and by the time they are felt, recession has already arrived.

Another way to think about how we arrived at this economic climate, is remembering that we have had a decade of nearly 0% interest rates (essentially free money) and additional stimulus injected as a result of the pandemic. The decade of free money allowed investors to fund loss making ideas for longer, nearly becoming a norm given the length of the regime. Most of these policies have never been experimented with before, therefore the effects are unknown, and often take time to see the results in the economy.

An excerpt by Todd Ahlsten, recorded in Barron’s magazine (January 13, 2023) sums up the post pandemic dynamic well:

“I worry about overextrapolating trends. That’s a theme I thought about coming into this meeting. In 2021, we had an epic peaking in conditions, such as zero to negative interest rates and ample liquidity, that made things perfect for the overextrapolation of secular growth. Now we may be over-extrapolating inflation dynamics and forgetting about a lot of long-term trends that are deflationary. Scott made some important points about demographics. Negative demographic trends, high debt, wealth inequality, and the productivity of technology haven’t gone away. They have merely taken a back seat because of all the stimulus jammed into the economy during the Covid pandemic in 2020.

Today, liquidity is being reduced at the same time that the Fed has been raising rates at the most rapid rate in generations, so we are going to have an economic cycle. Like Scott, we see inflation coming down, although it will be a nonlinear decline. At the end of the year, we could see the 10-year Treasury yield below 3%, maybe as low as 2%.

Investors often mistake the cyclical for the secular, and vice versa. In 2021, they often priced cyclical growth as secular growth, and now there is a tendency to price secular growth as cyclical.”

For the year ahead, it is apparent that economic performance is dependent on the Fed’s war on inflation. The Fed continuously communicates that they are ‘data dependent’ meaning that as data does provide evidence that inflation is moving down to their 2% target, the data will guide their future policy decisions.

Individuals’ savings are diminishing, though started off at historically high levels, meaning they will be in a better financial position, for longer, than in the past. Corporate and Bank balance sheets, by and large, are strong and cash rich suggesting that systemic risks are lower than in the past.

Questions to determine this years fate are: Is the engineered slowdown successful? Is the Fed able to ease their restrictive policy to a more neutral one, as inflation abates? Is the elusive ‘soft landing’ that nearly nobody believes is possible, possible?

—

For reference, visit:

AAII Sentiment Survey

Chicago Fed NFCI

Barrons Roundtable

—

The opinions expressed in this blog are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual or on any specific security or investment product. It is only intended to provide education about the financial industry. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Please review full disclosure at link, below.

2023: In like a lion, out like a lamb?

You name it. 2022 was the worst year for [Insert favorite Asset class] since [Insert historic year], and you’re probably correct. One that’s commonly quoted is that it was the worst year for the 60% Stock / 40% Bond portfolio since 1936. We can agree that 2022 was a painful year for most asset classes. Inflation accelerated for the better part of the year, and Central Banks, globally, got serious about addressing it.

Just over a year ago, the U.S. economy was booming, job openings were abundant and difficult to fill. Housing was setting price and sales records, and goods inventory was nonexistent for items from cars to furniture.

We enter 2023 with fear and pessimism in the air. Inflation, job loss, bankruptcies, and debate of recession on the horizon populate the headlines. The AAII (American Association of Individual Investors) Sentiment Survey offers insight into the opinions of individual investors, depicted in the chart, below. Individual investor pessimism in 2022 reached levels typically seen only during the worst of recessions.

In response to historically fast rise in inflation, the Federal Reserve completely changed its stance on monetary policy from the extremely accommodative one in place since the onset of the pandemic. The Federal Funds rate of 0.25% at the beginning of 2022 was increased to 4.5% in one of the fastest rate hiking periods in history. In fact, inflation seemingly shocked the Fed so much, that in May 2022 Chairman Jerome Powell communicated that a 75 basis point rate hike was not being ‘actively considered’, then went on to increase rates by 75 basis points at each of the next three meetings.

Additionally, the Fed’s bond buying policy (Quantitative Easing (QE)) shifted to a bond selling (Quantitative Tapering (QT)) policy. For reference, when the Fed buys bonds, it is injecting liquidity to the economy (accommodative policy), and vice versa when selling bonds (restrictive policy).

This shift to a severely restrictive policy resulted in some of the tightest financial conditions of the last decade, with hopes of removing ‘excess financial slack’ present in the economy, causing inflation.

The economic slowdown that we’re now experiencing is one that is ‘engineered’ by the Fed. Due to the restrictive policies in place and tight financial conditions that have been instituted, we see a reduction in spending, production etc. that were inflationary consumer habits. Higher interest rates cause monthly payments on big ticket items (i.e. housing and cars) to increase, therefore resulting in a slowdown in purchases. Energy costs spiked in the early half of 2022, though are mostly below the levels entering that year (factors outside Fed policy have also affected Energy over the past year), further easing inflation metrics.

These dynamics of easing demand for goods are allowing the economy to rebalance itself, while for the time being not causing a systemic risk that can ‘break’ the economy leading to severe recession. Forecasters and the media often refer to the Fed’s ‘soft landing’ as the ideal outcome where the Fed is able to institute a restrictive monetary policy to reduce financial excess without causing a recession, or a mild one if so. It should be noted that this outcome is highly elusive as the effects of policy take time to be felt through the system, and by the time they are felt, recession has already arrived.

Another way to think about how we arrived at this economic climate, is remembering that we have had a decade of nearly 0% interest rates (essentially free money) and additional stimulus injected as a result of the pandemic. The decade of free money allowed investors to fund loss making ideas for longer, nearly becoming a norm given the length of the regime. Most of these policies have never been experimented with before, therefore the effects are unknown, and often take time to see the results in the economy.

An excerpt by Todd Ahlsten, recorded in Barron’s magazine (January 13, 2023) sums up the post pandemic dynamic well:

“I worry about overextrapolating trends. That’s a theme I thought about coming into this meeting. In 2021, we had an epic peaking in conditions, such as zero to negative interest rates and ample liquidity, that made things perfect for the overextrapolation of secular growth. Now we may be over-extrapolating inflation dynamics and forgetting about a lot of long-term trends that are deflationary. Scott made some important points about demographics. Negative demographic trends, high debt, wealth inequality, and the productivity of technology haven’t gone away. They have merely taken a back seat because of all the stimulus jammed into the economy during the Covid pandemic in 2020.

Today, liquidity is being reduced at the same time that the Fed has been raising rates at the most rapid rate in generations, so we are going to have an economic cycle. Like Scott, we see inflation coming down, although it will be a nonlinear decline. At the end of the year, we could see the 10-year Treasury yield below 3%, maybe as low as 2%.

Investors often mistake the cyclical for the secular, and vice versa. In 2021, they often priced cyclical growth as secular growth, and now there is a tendency to price secular growth as cyclical.”

For the year ahead, it is apparent that economic performance is dependent on the Fed’s war on inflation. The Fed continuously communicates that they are ‘data dependent’ meaning that as data does provide evidence that inflation is moving down to their 2% target, the data will guide their future policy decisions.

Individuals’ savings are diminishing, though started off at historically high levels, meaning they will be in a better financial position, for longer, than in the past. Corporate and Bank balance sheets, by and large, are strong and cash rich suggesting that systemic risks are lower than in the past.

Questions to determine this years fate are: Is the engineered slowdown successful? Is the Fed able to ease their restrictive policy to a more neutral one, as inflation abates? Is the elusive ‘soft landing’ that nearly nobody believes is possible, possible?

—

For reference, visit:

AAII Sentiment Survey

Chicago Fed NFCI

Barrons Roundtable

—

The opinions expressed in this blog are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual or on any specific security or investment product. It is only intended to provide education about the financial industry. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Please review full disclosure at link, below.